Math Instruction & Virtual Teaching: Does Face-to-Face Instruction Matter?

By Karajean Hyde

Co-Director, UCI Math Project

May 8, 2020

For a video presentation on how to most effectively use Pear Deck, featuring Karajean Hyde, please click here.

I’ve just spent the past few weeks in non-stop webinars and Zoom meetings, reading and begging for help to learn how to use the following: Zoom with chat features, Zoom with breakout rooms, Pear Deck, Yuja, Screencastify, Interactive Google slides, Google forms with QR codes, and countless other technologies. Why? So I can teach remotely, students can still interact, we can measure learning, and we can provide appropriate support. Oh, and while doing all of this, I’m also homeschooling my own four children. No problem, right? If and when we each can perfect our virtual instruction, will it yield the same results as face-to-face instruction?

One of the reasons we have Common Core math standards is that the evidence was clear that over 80% of everything learned in pre-common core, K–12 math classrooms in the US could be done by a computer; the standards represented a shift away from merely copying steps as a computer does and towards problem solving and rigorous conceptual learning. Where does that leave us, now, when distance learning is dependent upon computers and zoom calls? Can we still expect Common Core level rigor and understanding? When we end our massive shut-down and the dust settles, it will reveal something about the value of teachers and administrators in real classrooms and schools.

Before school closures, some teachers regularly made use of technology as a significant part of their instruction, pushing out computer-based assignments and instruction, and then pulling small groups with the students who struggle to learn independently on the computer. In essence, this type of instruction can be fully replicated remotely now. In the absence of the early morning wake-ups, the hectic hustle of each school day, and the social challenges school settings can bring, we are forced to ask ourselves, what is the value of face-to-face instruction? Why would parents want to send their children back into our schools (other than eliminating the parental struggle of balancing working from home with children who have many needs)? The reason? Face to face instruction matters! Administrators and teachers make a major, positive difference in both student learning and the emotional well-being of our children! What can teachers and administrators do that a computer can’t? Let’s consider one major research tenant from math that also applies to other subject areas.

Math is best learned and retained in our long-term thinking memory (“declarative memory”), when it progresses from the concrete to the pictorial to the abstract. Why is face-to-face teaching crucial? Students need to learn with concrete objects, which we can’t replicate remotely. Even if manipulatives can be accessed at home, students cannot share their struggle or variety of approaches with each other which greatly enhances learning. My second grader learned to subtract at home with base-10 blocks this past week, but she was only privy to how she thought about it, lacking the opportunity to interact with all types of learners and thus broaden her understanding. While some hands-on instruction can be emulated online by using virtual manipulatives or drawing, teaching this way means excluding a critically important component of math learning: concrete.

Since math learning is best face-to-face in real schools, can any learning happen now? Our recommendation is to consider which types of lessons, based upon the 4 Types of Knowledge, are most adaptable to our current learning environment.

- Factual knowledge (recall): this can easily be maintained through online practice.

- Procedural knowledge: this involves following a set of steps or procedures, which can be modeled and practiced online.

- Conceptual knowledge: This involves experimentation with hands-on learning, discussions and sharing of different perspectives, all guided by the teacher as students progress from that concrete to the pictorial and clearly see the bridge to the abstract. We can try to do some of this remotely, but without the hands-on, real-time ability to see and discuss what others are doing, this will not be nearly as effective as face-to-face.

- Relational Knowledge (Problem Solving): As this requires productive struggle (for the student, not parent!), student collaboration and sharing of different ideas, this is also much less effective in virtual learning environments.

So which tools are the best to be using and for what purpose?

- Facts and procedures can be taught by making use of free pre-recorded videos (even by a teacher) and lessons for topics that can/should be taught by direct instruction (e.g. Khan academy or Delta Math). Worksheets for practice or analyzing student work can also be found free of cost and pushed out remotely for procedural practice. Teachers can then use virtual office hours to support specific students.

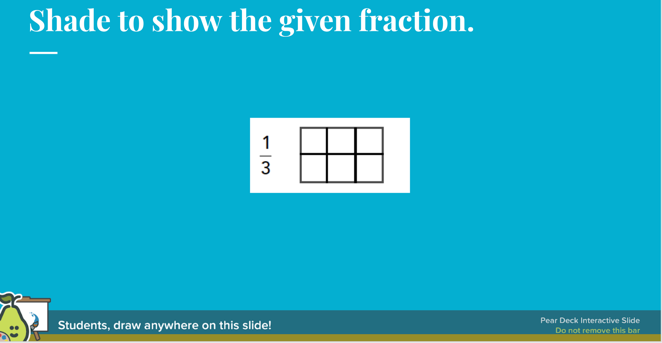

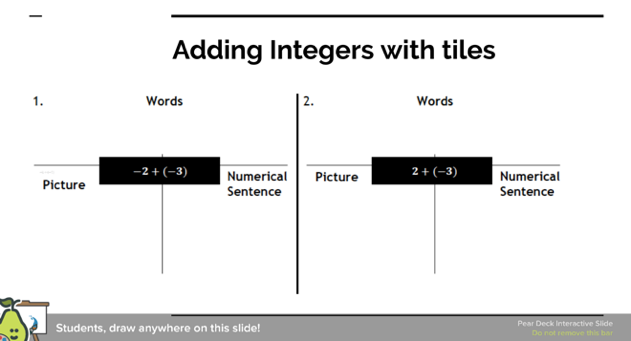

- Concepts can be taught to some extent, but will need to be so at least partly live. We can’t make-up for the concrete, but for some topics, we can use the pictorial. Consider using tools like Pear Deck (currently a free add-on in Google Slides) in which students “draw” onto images or slides to show/build understanding (pictorial) before getting to the abstract (Image 1). This tool also allows teachers to monitor student understanding by having them answer with numbers, text or drawing onto slides and allowing teachers to display student work for discussion and group learning. Pear Deck can be student paced on their own time and then live time can be used to share and discuss different ideas and pictures. Ideally, though, teachers will use this live as well. Desmos is also an excellent choice for this type of instruction (pre-made lessons or creating your own).

Image 1

- Problem Solving (and Concepts as discussed above) should be taught live. Zoom is a great tool for this as students can have silent think-time, can reply via chat, and can use break-out options to work in groups of 2–4. In these groups, teachers can oversee by having students collaborate on a Google doc to see progress. Live instruction time should focus on students sharing thinking and methods (such as number talks or results from an activity assigned). Note: if able, using Pear Deck Teacher Led along with Zoom is ideal for concepts and procedures.

As I ended my first lesson taught virtually, I reflected on how it went compared to my usual in person classes. I had checked all the boxes for what is considered good instruction: everyone stayed engaged the entire three hours; all my technology worked and I was able to manage the four screens switching between in-person instruction with a “function box” (whole class visual) and screensharing my Google slides with Pear Deck; and my pre-post assessment revealed that every student learned and 90% reached mastery with the topic…yet, I felt empty. Despite doing everything I could, nothing compares to the human interaction and the meaningful learning that comes from face-to-face instruction. There’s just something about seeing students struggle with using manipulatives and supporting one another, hearing their laughter in real time, and seeing their faces light up when they finally understand something. Face to face schooling will never lose its importance because it’s how people learn best, not behind a computer screen.

When we get back to “real” school, what will be your lasting lessons from this time at home? Will you “push out” assignments and serve as a babysitter/tutor? Or will you take the harder road, providing students what they really need: base-10 blocks, Play-Doh, or algebra tiles, and outdoor opportunities to model math on physical number lines and running and throwing balls to collect data for analyzing? Will you be content with quiet, individualized learning or will you revel in the chaos and noise of students collaborating and sharing incoherent explanations that somehow turn the light bulb on for another student? What value will you add to your students’ lives and learning when you get back into a physical classroom?

As you’re adjusting to our new reality, anticipate the day you get to be back “in school.” Let’s renew our commitment to providing the type of instruction that allows all students to understand the “why” and the “where did it come from” of the mathematics. For now, focus math instruction on what can be done remotely in a meaningful way, and consider saving as much of the conceptual learning and problem solving you can for when we can teach face-to-face again. In the meantime, know that you MAKE a DIFFERENCE in the lives of the students you teach.

Sources: Sousa, David. How the Brain Learns Mathematics. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin, 2015.

Teaching Inquiry-Based Math Virtually, Using Pear Deck

This introduction to Pear Deck will allow you to experience different ways to lead inquiry learning virtually and formatively assess students by allowing them to share their thinking in real-time (synchronously) or asynchronously (through student self-paced lessons).

Karajean Hyde is Co-Director of the UCI Math Project